Historic, Beautiful Community of Rugby, Tennessee

History of Rugby

Rugby, originally conceived as a class-free, agricultural community for the younger sons of English gentry, was named after Thomas Hughes’ alma mater in England. One of the best things about Historic Rugby is that though most colonists left by 1900, enough people remained to ensure its survival.

Starting in 1880, it was at its peak in the mid-1880s, with about 300 people living in the colony. More than 60 buildings of Victorian design graced the townscape on East Tennessee’s beautiful Cumberland Plateau. Hughes originally envisioned this community as a cooperative enterprise, with a cultured, Christian lifestyle, free of the rigid class distinctions of Britain.

The idea for the colony grew out of Hughes’ concern for the younger sons of landed British families. Under the custom of primogeniture, the eldest son usually inherited everything, leaving the younger sons with only a few socially accepted occupations in England or its empire. In America, Hughes believed, these young men’s energies and talents could be directed toward community building through agriculture. The townsite and surrounding lands were chosen partly because the newly built Cincinnati-Southern Railroad had just completed a significant line to Chattanooga, opening up this part of the Cumberland Plateau.

Rugby both flourished and floundered in the 1880s, attracting widespread attention on two continents and hundreds of hopeful settlers from both Britain and other parts of America. By 1884, Hughes’ vision seemed close to becoming a thriving reality. An English agriculturalist had been employed to help train new colonists. Some 65-70 graceful Victorian buildings had been constructed on the townsite, and over 300 residents enjoyed the rustic yet culturally refined atmosphere of this “New Jerusalem.” Literary societies and drama clubs were established. Lawn tennis grounds were laid out and used frequently. Colonists and visitors enjoyed rugby, football, horseback riding, croquet, and swimming in the clear flowing rivers surrounding the townsite. The grand Tabard Inn, named for the hostelry in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, soon became the social center of the colony. The Thomas Hughes Public Library, with thousands of volumes donated by admirers and publishers, was the pride of the colony. Rugby printed its own weekly newspaper.

General stores, stables, sawmills, boarding houses, a drug store, dairy, and butcher shop were all in operation.

During this heyday period, two trains a day ran to Cincinnati, providing a link to goods, services, and entertainment for the Rugby colonists and the town’s many visitors. Press in both America and Europe carried frequent updates on the colony’s progress and problems.

A typhoid epidemic in 1881, two inn fires in 1884 and 1889, and more affected the community. Thomas Hughes – whose aged mother Margaret Hughes, brother Hastings, and niece Emily lived in Rugby during its early years – managed to spend only a month or so each year in the colony.

He poured more than $75,000 of his own money into the effort to build the community in the wilderness.

Despite the problems, Hughes never gave up on Rugby’s future. In a letter to some of the remaining settlers shortly before he died in 1896, Hughes wrote poignantly: “I can’t help feeling and believing that good seed was sown when Rugby was founded and someday the reapers, whoever they may be, will come along with joy bearing heavy sheaves with them.”

By 1900, most of the original colonists had left, many for other parts of America. Though Rugby declined, it was never deserted. Individual residents, some children of original colonists, struggled over many decades to keep its fascinating heritage alive, its surviving buildings and lands cared for, and its story told.

Today Rugby is both a living community and a fascinating public historic site run by Historic Rugby, offering visitors a museum, historic building tours, lodging, stores & an events center. It has been open to the public since 1966 as a non-profit 501 (c) 3 site and is recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

There are many of the original buildings nestled between the Big South Fork National Recreation Area and the Rugby State Natural Area, surrounded by rugged river gorges and historic trails.

Tours

By reservation only for groups of 10 minimum. Please note tour times (all Eastern) Thur/Fri/Sat 9,11,1,3 & Sun 1&3 EDT

Call for info on groups*

$7 Adults

$6 Seniors

$4 Students

Preschoolers Free

* Group, school rates, and specialty tours are always available (even during the off-season)!

Please call our office at +1(423) 628-2441 Ext. 1 to schedule your next group trip and for daily information!

Award- Winning Documentary

We also offer an award-winning documentary, The Power of a Dream, before one of our guides walks you back into history through four original historic buildings, telling the stories of inhabitants and providing informed commentary on the village through its founding up to the current community.

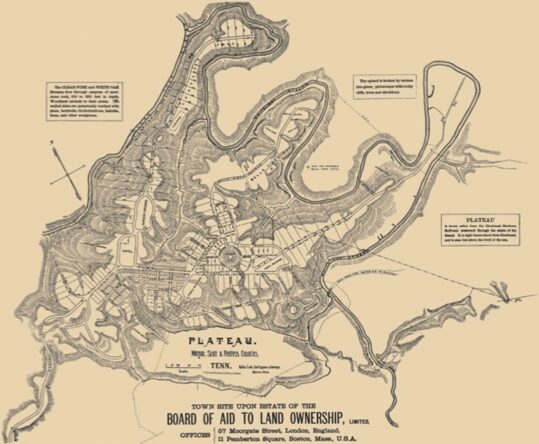

Maps

In addition to historical tours, you’ll find maps of the village & Rugby State Natural Area trails, activities within the area, and popular Appalachian destinations, including the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area & its trails within Rugby plus trails within the Rugby State Natural Area.